The Origins of Islamic Intolerance

How is it possible to explain the hatred and violence that was so horrifically brought home to the United States on September 11th?

To understand 9/11 requires an understanding of Islamic history, or more specifically, the rise and fall of the Islamic world from the heights of scientific and philosophical greatness prior to and during the Moorish Empire in Spain and North Africa to a state of decadence and stagnation that has left the Arab Middle East a cultural backwater with massive poverty, illiteracy, a repressed middle class, and a collective Gross Domestic Product (GDP) less than that of a single Western country – Spain.

In the eyes of the Muslim world, it is the West that is to blame. That attitude is now common in the Middle East with villains ranging from the Mongols to Anglo-French imperialists to the Jews to Islam itself.

–break–

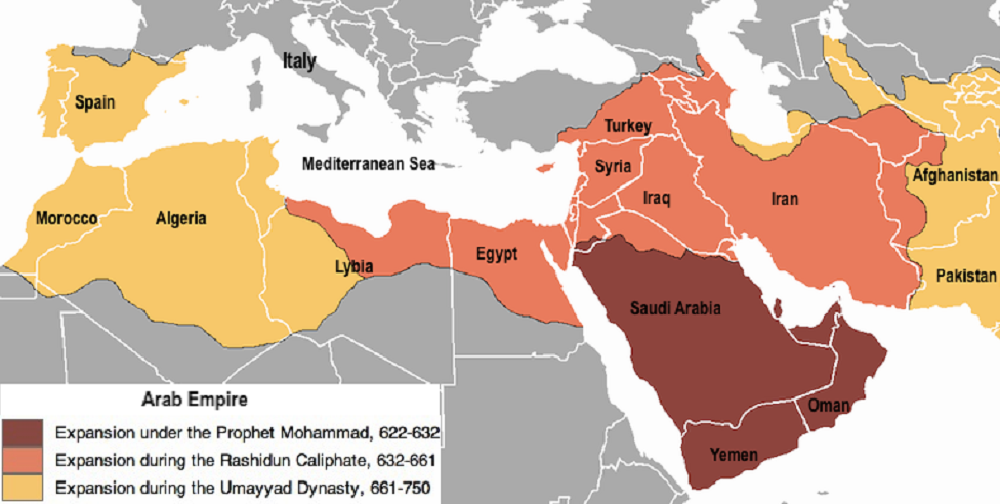

Islam arose in the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century. Like Christianity, Islam officially condemned forced conversions. But unlike Christianity, Islam instructed its followers to ensure that the world was under the political control of the Faithful. Hence, Islam’s political domination could be, and was, spread by the sword. Islamic calvaries burst out of Arabia and quickly took control of the Middle East, Byzantium and Persia. The Middle Eastern armies of the Christian Byzantine Empire were defeated and annihilated in 636, and Jerusalem fell in 638. By the early 8th century Arab Islamic forces had reached the Straits of Gibraltar and crossed into European Spain. By 712, they had reached the center of the Iberian Peninsula, and by the 730’s, they were raiding deep into the heart of France.

To understand the depth of hatred Islamic fundamentalists feel for the West, one must understand the nature of the majestic civilization that the Arabs built in Spain during the time of their Moorish Empire – and the degree to which the Arab world today has fallen in virtually every field of human endeavor since then.

The Moorish Empire

For centuries, the world view and self-view of Muslims seemed well grounded. Between the end of antiquity and the early modern period, Islam represented the greatest military power on earth and was the foremost economic power in the world, trading in a wide range of commodities through a far-flung network of commerce and communications in Asia, Europe, and Africa; importing slaves and gold from Africa, wool from Europe, and exchanging a variety of foodstuffs, materials, and manufactured goods with the civilized nations of Asia.

It had achieved the highest level in the arts and sciences of civilization to that point in human history. Inheriting the knowledge and skills of the ancient Middle East, of Greece, and of Persia, it added to them new and important innovations from outside, such as the use and manufacture of paper from China and the decimal system from India. It is difficult to imagine modern literature or science without one or the other.

It was in the Islamic Middle East that Indian numbers were, for the first time, incorporated in the inherited body of mathematical learning. Today, they are still known as “Arabic numerals.” To this rich inheritance, scholars and scientists in the Islamic world added an immensely important contribution through their own observations, experiments, and ideas. In most of the arts and sciences of civilization, medieval Europe was a pupil and in a sense a dependent of the Islamic world, relying on Arabic versions even for many otherwise unknown Greek works.

While what is now the Western world floated on a sea of superstition, the Arab-Muslim Empire of Spain was busying itself probing the limits of the arts and the sciences rather than dwelling on its own sense of victimhood (as it does today). Its contributions to the fields of astronomy, mathematics, medicine, literature, physics, architecture, sociology, philosophy, botany, metallurgy, animal husbandry and astrology were instrumental in laying the foundations for the European Renaissance.

The Moorish Empire of the Middle Ages encouraged free thought, experimentation, discussion and evaluation. It put the study of medicine on a scientific footing by eliminating superstition, introducing Medical Codes of Conduct, requiring the introduction of examinations and the taking of the Hippocratic Oath.

This Empire produced scientists and scholars who developed the astrolabe for those who navigated the world’s oceans; determined the earth’s circumference; produced books on astronomical tables that were used by European scientists for the next four centuries; created Algebra (Al-Jabr wa…) along with the theory of sine, cosine and tangent.

It developed the principles of modern surgery; constructed the first “globe” of the known world; made major advances in the field of modern chemistry (or alchemy – a derivative of the Arabic word “al Kimiya”) – including the development of dosage standards (prescriptions) for patients including the process of chemical preparations for medicines.

It advanced the concept of “contagious” diseases (which, until that time, had been thought to originate only from within the body itself); developed the tables outlining the “angles of refraction” leading to an explanation of, among other things – twilight; established laboratories for long term experimentation and pioneered new methods of observation and measurement.

The Moorish Empire also indelibly left its intellectual imprint in the heavens as one may see whenever one reads the names of the stars on a modern-day celestial globe.

The Great Decline

The classic work of Bernard Lewis, Professor of Near Eastern Studies Emeritus at Princeton University titled What Went Wrong goes far to explain the great decline of the Moorish Empire to the cultural backwater that is now the Arab Middle East today.

He details how massive social, economic and scientific changes in the West barely made a ripple in the Muslim world for almost a millennium, and only with the dawn of the 20th century did the Muslim world begin to realize the implications of their backwardness – illiteracy, poverty and political and religious repression.

And when the Arab regimes of the Middle East finally realized that Islamic society had been eclipsed both culturally and militarily by the West, they chose to portray themselves as ?victims,? searching for scapegoats and excuses, rather than confronting their own inadequacies.

The fascinating case he makes is that the early success of Islam was actually a curse rather than a blessing, in that it had the effect of retarding the development of the Muslim Middle East resulting in a particularly negative reaction to the rise of world dominance by the West.

As the Reformation, the Renaissance, the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions took root in Western Europe (beginning in about the 16th century and accelerating through the 19th and 20th centuries), the West grew in wealth, power, scientific and technological accomplishment. It fought its religious wars and ultimately separated church from state (which most Arab Muslim states have yet to do).

This resulted in the creation of a new, educated, secular, free thinking middle class unfettered by religious dogma, who were prepared to challenge ancient traditions of learning in virtually every field of human endeavor – art, literature, astronomy, mathematics, chemistry, scientific research and philosophy – in an era that we know today as the Renaissance.

It was this Renaissance that led to the technological and scientific supremacy of Western civilization, the transformation of public institutions, the rise of individual freedom and responsibility, and it left the Islamic world behind.

Lewis argues that the success of Muhammad in establishing not merely the Muslim religion, but also a state dominated by that faith, served to create a society that was totalitarian by its very nature, bound by rules and strictures that made it “too static to adapt and compete with a West where Christianity, after the Reformation and the Renaissance, did not demand control over the political and economic spheres.”

In short, Islam, by never separating church from state retarded the development of a freethinking, educated, secular middle class – the foundation stone upon which modern technology, invention and enterprise are built.

Because of this ?non-evolution,? the Islamic faith itself became implicated in the decline of Islam relative to the West.

Muslims were taught to regard Christianity as inferior to Islam. As a consequence, it was argued that ?one does not go forward by going backward.? They simply didn’t think that much of anything useful could be learned from these infidels. After all, Islam represented the final and true faith, and Christianity and Judaism were just flawed precursors. The Arabs assumed that the only knowledge that a Muslim needed to acquire was that of Islam. Knowledge was merely interpreted as “knowledge of Islam,” and the study of other kinds of knowledge was regarded as either sinful or as lacking in merit unless it contributed to the afterlife. As a result, the pursuit of knowledge as we know it in the Western world (other than the knowledge that flows directly from Islam) was neglected.

So when the rulers of the Ottoman Empire, which controlled the Islamic heartland from the 14th century until World War I, finally perceived the threat posed by the Europeans, they responded by importing the latter’s guns and military advisers and factories but not the latter’s values.

As a result, many Muslims chose to blame the historical fate of the Islamic world on the actions of foreign powers, above all European imperialism starting with the Crusades and carrying through to the colonial era, and, later, Zionism, Israel and the U.S.

The Rise of Islamic Fundamentalism

For many secular Arab ideologists, the defeat by Israel in the Six-Day War (1967) was another dramatic illustration of the crisis of Islam: lethargic, backward Muslims defeated by a modern enemy. Thus it was only natural for the debate about Islam to reemerge in the aftermath of the 1967 defeat.

In the aftermath of defeat, the turning of the masses to religion for solace and consolation and the continual appeal, couched in religious terms, served as a reminder that God may be dead elsewhere else, but He was alive and well in the Arab world. The fundamentalists argued that the Arabs had lost the war because they had lost their faith and direction. They had disconnected themselves from a deeply held system of beliefs. Thus, the Arabs proved an easy prey to Israeli power.

They argued that Islamic society needs a rigid system of beliefs, an ideology to guide it. Their contention was that a strict fundamentalist interpretation of Islam offered that system of beliefs and could do what no other imported doctrine could hope to do – mobilize the believers, instill discipline, and inspire people to make sacrifices and, if necessary, to die for the cause through martyrdom.

The fundamentalists argued that the Muslim world was now being challenged by another crusade – one that sought to penetrate the mind of the Muslims and to rearrange it.

Thus, although Lewis does not address the issue, failing to bring Islam into the modern era has played a major role in the rise of Islamic fundamentalism.

By all the standards that matter in the modern world — economic development, job creation, literacy, education, scientific achievement, political freedom and respect for human rights — what was once a mighty civilization has indeed fallen… and there is no mistaking the growing anguish, the mounting urgency, and of late, the seething anger that has resulted.