Europe’s Hezbollah Dilemma

The long-awaited results of the Bulgarian investigation into the Burgas terrorist bombing last July 18th has placed enormous pressure on the European Union to proscribe Hezbollah as a terrorist organization – a classification repeatedly called for by the U.S., Canada and Israel, but so far rejected by EU member states except the Netherlands which has listed it as such since 2008.

Hezbollah’s involvement in the Burgas tragedy should make European leaders rethink the standard excuses they have made to rationalize their lack of action against Hezbollah. One often-quoted EU excuse maintains that since Hezbollah in Lebanon has both a military aspect and a political/social aspect, clamping down on the former would cripple the latter and destabilize the Hezbollah-dominated government of the country. Since when did Hezbollah become a charitable organization like Oxfam or the Red Cross? As the Chicago Tribune pointed out recently: “Hezbollah’s idea of investing in the next generation is to acquire 50,000 missiles – more than many NATO members possess – and stockpile them in the immediate vicinity of schools and playgrounds. It doesn’t take a Nobel Peace Prize laureate to realize that this isn’t exactly a selfless humanitarian organization.” The irony is that even in Lebanon, Hezbollah is not considered to be a Lebanese party whose mission is to protect the country. It is seen by the vast majority of Lebanese as a dangerous militia that has chosen to use Lebanon as its geographical base from which to launch attacks against Iran’s enemies no matter who or where they are. Nothing more.

While this hair splitting gives Hezbollah the wiggle room it needs to carry on its nefarious activities in Europe, the argument has no validity given that the EU’s terror list already includes Hamas, which won the Palestinian legislative elections in 2006, as well as the Communist Party of the Philippines, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and other radical organizations that are involved in their countries’ political systems. And given that the EU has already sanctioned individuals and entities “responsible for the violent repression against the civilian population in Syria”, there is no logical reason to exclude Hezbollah as it clearly falls into this category given its continuing support of the Assad regime.

This argument is especially specious given that Hezbollah’s second-in-command Naim Qassem has already rejected the British separation of his organization into political and military wings. Qassem told the Los Angeles Times in 2009: “The same leadership that directs the parliamentary and government work (in Lebanon) also leads jihad actions in the struggle against Israel.”

Stripping away all this double-speak, EU member states, most notably France and Germany, fear that proscribing Hezbollah as a terrorist organization could potentially lead to the activation of Hezbollah terror cells and retaliation across the continent. According to Matthew Levitt, the Director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s counterterrorism and intelligence program, the Europeans are afraid to stir up a hornet’s nest. “Hezbollah” he writes, “is not very active in Europe and the Europeans feel that if you poke Hezbollah or Iran in the eye, they will do the same to you. If you leave them alone, then maybe they will leave you alone.”

France is particularly apprehensive given the exposure of its UNIFIL forces in Lebanon to Hezbollah fire, and it is even more concerned that designating Hezbollah as a terrorist organization would, once again, bring Hezbollah/Iranian-directed terrorism back to its streets.

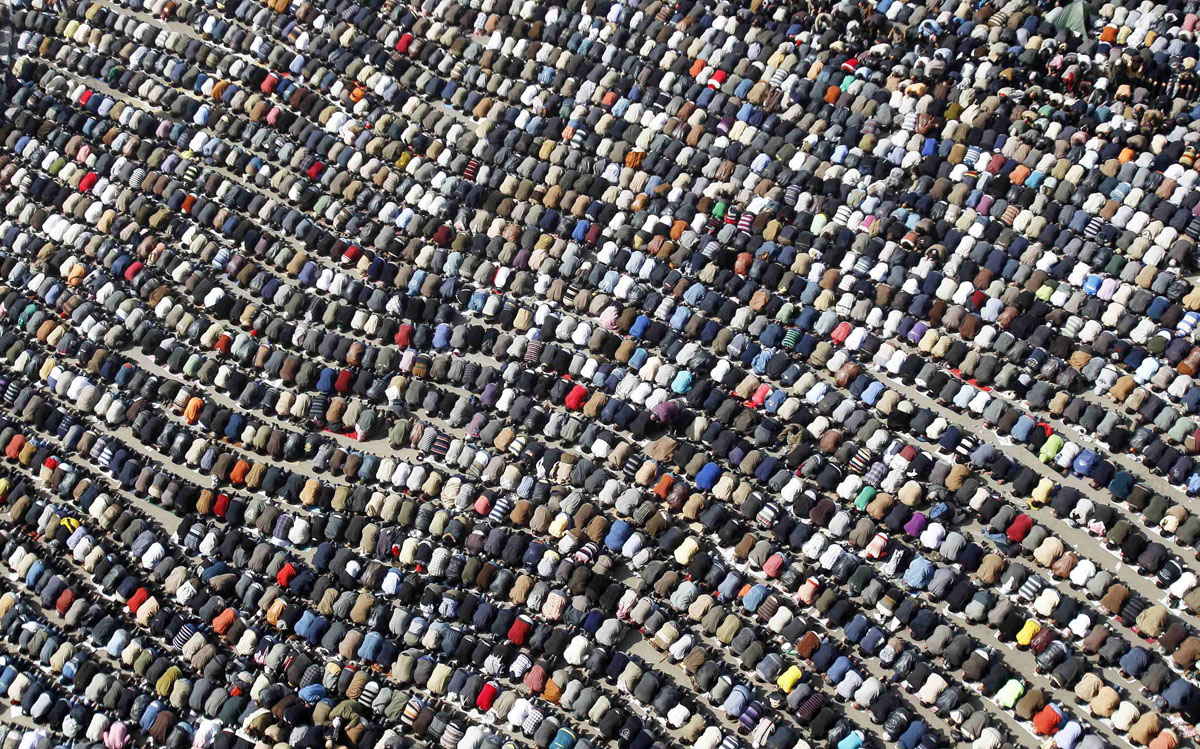

Their fear is not entirely unjustified. Millions of Muslim and Arab immigrants are emerging as a major political force in Europe and many sympathize with the Shiite organization’s war on the “infidels”. After all, Hezbollah was created by Iran in 1982 as a “weapon” to aggressively export the late Ayatollah Khomeini’s “Islamic Revolution” among Shiites in Lebanon, Arab countries and throughout Muslim immigrant communities in Europe. Even former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage considered Hezbollah the “A-Team of terrorism”. Prior to 9/11, it had murdered more Americans than any other terrorist group and it has attempted and/or perpetrated terror attacks on its own and in conjunction with its Iranian benefactors in Argentina, Britain, India, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Greece, Kenya, Cyprus, Israel, Thailand, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon, in addition to its illegal albeit lucrative activities in Latin America and West Africa.

In the Middle East, it has acted as a proxy for the Syrian and Iranian regimes, receiving money and weapons from both in return for “services rendered” including its complicity in the assassination of the anti-Syrian former Lebanese Prime Minister, Rafik Hariri, in 2005. In July 2011 the United Nations Special Tribunal indicted four senior Hezbollah members for the murder. Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah called the four terrorists “brothers with an honorable past” and threatened that he would “cut off the hand” of anyone who will try to extradite them.

In Europe, however, Hezbollah has maintained a relatively low profile since the mid-1990s, quietly holding meetings and raising money that goes directly to Lebanon not only for building schools and clinics, and delivering social services, but for financing its global terrorist activities against Israel on behalf of its Iranian masters. In January 2010, Der Spiegel noted that Hezbollah was “using drug trafficking in Europe to fund part of its activities.” In one case, the German police arrested two Lebanese citizens after they transferred “large sums of money to a family in Lebanon with connections to Hezbollah’s leadership.” German authorities also found 8.7 million Euros in the bags of four other Lebanese men at the Frankfurt airport in 2008. The money contained traces of cocaine.

Hezbollah operatives, using Europe as a base for money-laundering and fundraising, are deployed throughout Belgium, Bosnia, Britain, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, India, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, and Ukraine with an estimated 950 members in Germany alone according to a 2011 report issued by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. While European security services maintain surveillance on Hezbollah’s political supporters, experts say they are ineffective when it comes to tracking Hezbollah sleeper or sabotage cells that pose the greatest danger.

According to Alexander Ritzmann, a policy adviser at the European Foundation for Democracy in Brussels, who testified before Congress on Hezbollah: “They have real, trained operatives in Europe that have not been used in a long time, but if they wanted them to become active, they could.” And therein lies the European dilemma. In 2007, James Phillips, writing for The Heritage Foundation, noted that Hezbollah terrorist attacks against Europeans began decades ago: “The October 1983 bombing of the French contingent of the multinational peacekeeping force in Lebanon (on the same day as the U.S. Marine barracks bombing), which killed 58 French paratroopers, the single French worst military loss since the end of the Algerian War in 1962; the December 1983 bombing of the French Embassy in Kuwait; the April 1985 bombing of a restaurant near a U.S. base in Madrid, Spain which killed 18 Spanish citizens; a campaign of 13 bombings in France in 1986 that targeted shopping centers and railroad facilities, killing 13 people and wounding more than 250; and a March 1989 attempt to assassinate British novelist Salman Rushdie that failed when a bomb exploded prematurely killing a terrorist in London.”

Author Eli Karmon of the Institute for Counter-Terrorism in Herzliya went even further: “In the negotiations concerning the end of the wave of Hezbollah/Iranian attacks in France, Iran’s main demands included the release of a number of Iranians detained in France on charges of terrorism; the renegotiation of a $1billion loan from Iran to France, frozen when French assets were seized by Iran during the 1979 revolution; and the cancellation of French weapons sales to Iraq. France surrendered on all fronts and all the terrorists were freed. In 1990, five Iranians led by the Lebanese Anis Naccache, convicted ten years earlier of trying to kill former Iranian Prime Minister Chapur Bakhtiar, were pardoned. In August 1991, in spite of its promise to stop terrorism on French soil, Tehran organized the successful assassination – in Paris – of the same Chapur Bakhtiar.”

In the final analysis, however, while fear of reprisal is both psychologically understandable and perhaps even morally defensible, turning the other cheek will not deter and has never deterred this terrorist organization. The EU’s anti-terror policy cannot be based on the false hope that Hezbollah will try to avoid killing European bystanders at home and abroad as it carries out its terrorist attacks. Without a strong reaction to the Burgas attack, Hezbollah will understand that it can attack any group with impunity so long as it is feared.

Freezing Hezbollah assets and bank accounts in Europe and imposing EU sanctions would deprive the organization of its European funding sources and operational freedom. It would facilitate cross-border cooperation in apprehending and arresting Hezbollah operatives in Europe and Hezbollah recruiters and operatives would be denied crucial entry to European countries. Weakening Hezbollah, which is already terrified by the prospect of losing its Syrian ally, not to mention regional isolation and facing a strategic dismemberment, would advance the EU’s policy goals in the Middle East. It would also be a blow to Assad’s regime and increase the chances of re-establishing a truly democratic Lebanon free of Hezbollah’s political and military stranglehold, not to mention a strategic victory over Iran and its plan for Shiite hegemony in the Middle East.

Alternatively, the failure to list Hezbollah as a terrorist organization will provide it with the opportunity to further organize, recruit, raise funds, and carry out additional terrorist attacks across the European continent and throughout the world. At this point, it should be clear to the Europeans, based upon their past experience, that terrorism cannot be appeased, nor can organizations that perpetrate it be defeated unless and until their supporting infrastructures have been shut down especially their political and financial front organizations.

Europe’s anti-terrorism policy should not be based on the false hope that, if left alone, Hezbollah will better calibrate its future terror attacks to avoid hurting European bystanders. This attitude is no different from that expressed by Winston Churchill when he said: “An appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile, hoping it will eat him last.” The Hezbollah crocodile has already consumed half of Lebanon and has sown seeds of destruction around the world. Contrary to their prevailing attitude, the Europeans will not be the last to be eaten. They will be among Hezbollah’s first victims.

Europe wants to treat Hezbollah as a legitimate political organization, but the organization’s activities and history place it squarely outside the realm of legitimacy. So long as Europe remains blind to this reality and allows the “Party of God” to conduct business as usual throughout Europe, it is guilty not just of hypocrisy, but of passive complicity in Hezbollah’s attacks on innocent civilians. Inaction on the part of the EU will transform Europe into a free-fire zone and Europeans will not be exempt from the slaughters that will ensue regardless of how long they continue to bury their heads in the sand.