A Leap of Faith: Analysis of the Israeli-Hamas Ceasefire Agreement

Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, Defense Minister Ehud Barak and Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman marked the Egyptian-brokered ceasefire with Gaza that went into effect on November 21st by announcing that the limited goals set for the operation had been achieved – eliminating Hamas missile sites and reinstating the Gaza ceasefire.

But were these goals achieved and, if so, are they broad enough to establish an enduring peace. According to the terms of the ceasefire agreement, Israel and Hamas agreed to halt “all hostilities.” Israel is restricted from deploying ground troops or targeting terrorist leaders in Gaza provided of course, that Hamas and its militias abide by the terms of the ceasefire. For Hamas that means an end to Israeli airstrikes and assassinations of its terrorist leaders. For Israel, it means a halt to missile fire from Hamas and its militias and an end to any further attempts at cross-border incursions into Israel from Gaza.

The agreement also calls for “opening the Gaza crossings, facilitating the movement of people and the transfer of goods, and refraining from restricting residents’ free movement.” In effect, it means that the self-declared security zone that Israel established along the Gaza border to prevent terrorist attacks no longer exists. It also means that the Egyptians will open the Rafah border crossing with Gaza and, at least on paper, take much more significant action to prevent arms smuggling into the enclave, although as one editorialist in Israel Hayom commented: “You would have to be an incorrigible optimist to believe that Egypt, under the leadership of President Mohammed Morsi, will do what Mubarak’s Egypt failed to do – fight terror. But still, the alternative is far worse.”

Israeli reaction to the ceasefire agreement appears split. The first group is satisfied that a ceasefire has been announced and that Operation Pillar of Defense has come to an end. The second is frustrated that Netanyahu acquiesced to international pressure and failed to destroy Hamas once and for all and re-conquer Gaza. According to a new survey conducted by the Dahaf polling institute immediately after the ceasefire was concluded, forty-three percent of Israelis feel this way.

On the positive side, Hamas’s command and control structures have been destroyed. Over the course of the operation, Israel launched more than 1,600 attacks, mostly precision air strikes against terrorist commanders and on missile squads, launch sites, tunnels, infrastructure, and government and communication facilities. The massive destruction wrought on Hamas’s war infrastructure also served to put Iran on notice that the U.S., in conjunction with its Israeli and Arab allies, intends to protect its interests in the Middle East and is determined to prevent any further Iranian incursions into the region – either through Hezbollah in Lebanon or in Syria. Israeli ambassador Michael Oren was correct when he told reporters that, in this battle, “Israel was not confronting Gaza, but Iran”.

Another positive element was that President Obama supported the operation and reiterated Israel’s right to defend itself – a fact that may prove crucial in the months ahead given that Iran has not abandoned its nuclear weapons quest and Israel will need U.S. support to destroy the centrifuges that have placed Iran on the fast-track to nuclear weapons capability.

Most importantly, Obama vowed to help the Israelis address their primary security concern (the smuggling of Iranian weapons and explosives through the Sinai into Gaza) by establishing along the Suez Canal and northern Sinai borders sophisticated electronic sensing devices and security fences managed by highly-trained U.S. security specialists. He also agreed, according to Debka sources, to deploy U.S. special forces in the Sinai peninsula. It was these latter undertakings and Morsi’s threat to terminate the 1979 Egypt-Israeli Peace Treaty that dissuaded Netanyahu, at the last moment, from invading Gaza. The hope of the Israeli government is that a strong and determined U.S. presence in the Sinai will deprive Hamas and its Salafist allies of the sophisticated Iranian missiles that could provoke Israel into invading the territory, overthrowing the Hamas regime, and re-conquering Gaza.

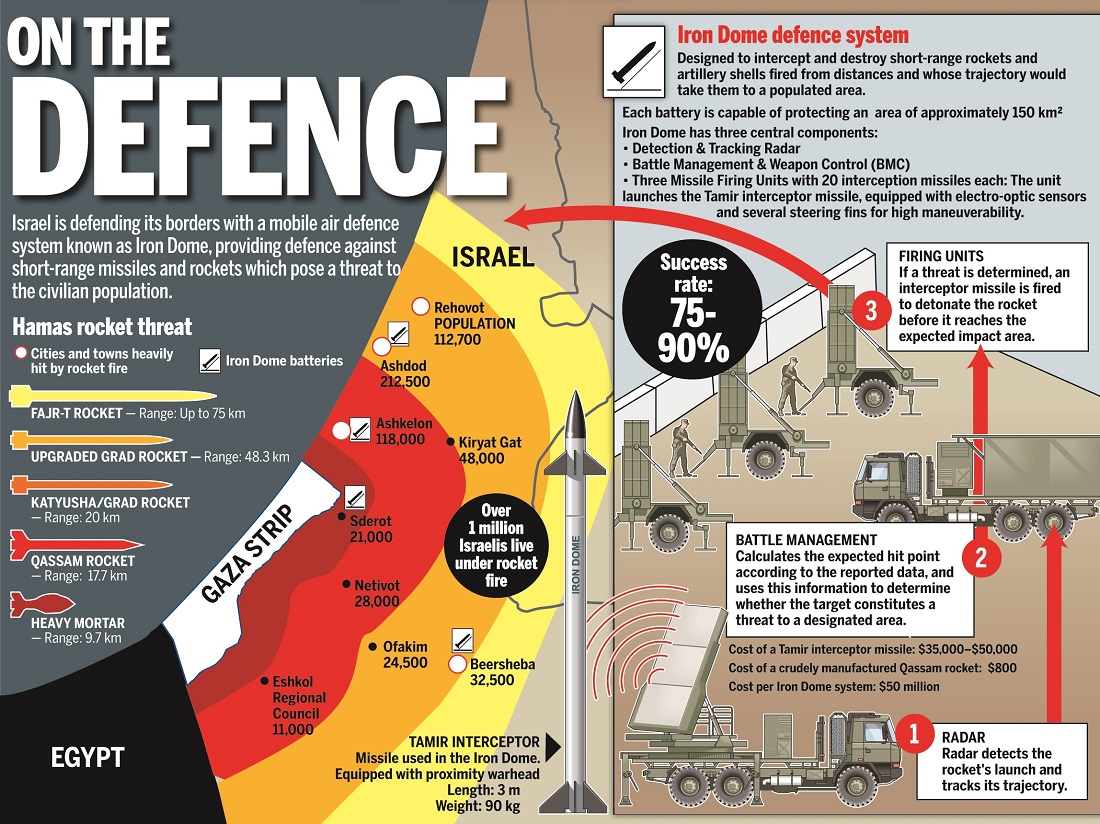

Obama also pledged additional funding for Israel’s anti-missile defense systems, including Iron Dome (for short-range rockets), David’s Sling (for medium- to long-range rockets) and Arrow (for long-range conventional ballistic missiles and high-altitude nuclear warheads).

In another positive aspect of the Operation, while one can find plenty of objectionable Western media coverage, the world media generally covered recent events in the Middle East in a more balanced fashion than it did during Operation Cast Lead in 2008-2009 by showing Israeli civilians under missile attack and published photos of Hamas using human shields and firing missiles into Israeli population centers from populated and protected areas – both of which are Hamas “trademarks” and war crimes under international law. When the first reports of Gazan civilian casualties came in, Western governments called on Israel to exercise “maximum restraint”, but there was no outrage at Israel’s offensive as in the case of Operation Cast Lead – most probably because the collateral damage was relatively low.

Finally, the impressive success of the Iron Dome anti-missile defense system (which intercepted more than 420 missiles, achieving a success rate of over 85 percent) not only protected 3.5 million Israelis under missile attack, but sent a clear message to Iran that its most advanced Fajr-5 missiles were no match for U.S./Israeli anti-missile technology while its own missile and enrichment sites were still vulnerable. The downside, however, is the high cost of Iron Dome (an estimated $40,000 per missile) and its limited number make it an ineffective weapon against a low cost “missile saturation” attack by its enemies. More importantly, the ability to repel enemy missiles is not an effective long-term strategy as it is essentially defensive in nature. Israel’s over-reliance upon ballistic missile defense could prove to be an existential strategic error.

Separate and apart from adopting a defensive strategy against aggressive jihadist enemies , there are other significant downsides to the ceasefire – downsides that have led many analysts to believe that the ceasefire is just a temporary respite and will allow Hamas the time to re-group, re-arm and re-train.

Operation Pillar of Defense was not the decisive victory most Israelis wanted and, as a consequence, Israeli deterrence may have been only partially restored. While Hamas sustained serious and devastating damage to its command and control structures, its military infrastructure, its communications networks and its arms manufacturing capabilities and weapons arsenals, its 15,000-strong militia remains largely intact and embedded within Gaza’s civilian population.

As a result, the moment the ceasefire was declared, Gazans filled the streets of Gaza City, as they did after 9/11, throwing candies in the air and proclaiming “victory over the Zionists” as they watched the residents of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv lie down on the ground or run to their safe rooms, stairwells and bomb shelters. Hamas will now boast that its “resistance” led to Israel’s agreement to end targeted killings and military operations in Gaza and the easing of restrictions on what can flow in and out of Gaza via land crossings and the sea – each of which are terms of the ceasefire agreement. In effect, Israeli concessions will be interpreted as flowing from Israeli weakness and eventually the perception of Israeli weakness will lead to a renewal of hostilities. Such is the culture of the Arab world.

Another concern arising from Operation Pillar of Defense (although not perceived as such by the Western media) is that Egyptian President Morsi has emerged as one of the key players in the Middle East. Considerable power has now been placed in the hands of a country that ideologically identifies with Hamas. Morsi’s Islamist government brokered the ceasefire and is now not only a regional mediator on good terms with the U.S. President, but also an arbiter between Israel and Hamas with U.S. blessings. As such, if any side has complaints against the other, it must turn to Egypt for mediation.

In accepting this provision, Israel has effectively deferred a major national security issue to a Muslim Brotherhood-dominated Egyptian government committed to Israel’s destruction. The Egyptian authorities had promised in their 1979 Peace Treaty with Israel to prevent “acts or threats of belligerency, hostility, or violence”, but nevertheless permitted massive smuggling of weapons into Gaza via tunnels and, no doubt, will continue to do so. Similarly, the Brotherhood’s goals have not changed since 1928 and there is no reason to expect Morsi’s Islamist government to do any better. According to the Brotherhood, Sinai is Egyptian and Islamic territory upon which the country has yet to exercise full sovereignty. It believes that the region must be “freed” from international agreements and treaties, specifically the peace treaty with Israel that declares the Sinai a demilitarized zone. In effect, the Brotherhood’s desire to develop the Sinai is only within the context of Egypt’s conflict with Israel. It intends to restore an Islamic caliphate, drive non-believers from the Middle East (most especially the Jews of Israel), and spread Islam throughout the world. For that reason, Morsi remains adamant in his refusal to speak with Israelis, has problems even uttering the word “Israel”, and supports the use of force against the Jewish state in order to liberate “Muslim lands.” On October 24th, when it was becoming clear that a showdown between Israel and Hamas was imminent, he gave a major address at Al Azhar University in Cairo where he stated that supporting Hamas in its struggle against Israel was a religious duty. He has convinced the Egyptian public that the treaty with Israel harms Egyptian national security and threatens internal Egyptian stability so, in the end, Egypt cannot be trusted on any account.

Egypt’s new mediation role is particularly worrisome given recent disclosures by Debka that Netanyahu avoided a final ground invasion of Gaza due, in large measure to Morsi’s threat to cancel the 1979 Peace Treaty with Israel. Israel’s problem is that Obama also cautioned Netanyahu against an invasion at his press conference in Thailand during the crisis when he said: “”Israel has every right to expect that it does not have missiles fired into its territory……If (the defense of Israel) can be accomplished without a ramping up of military activity in Gaza, that’s preferable. It’s not just preferable for the people of Gaza. It’s also preferable for Israelis, because if Israeli troops are in Gaza, they’re much more at risk of incurring fatalities or being wounded” and British Foreign Secretary William Hague added to the warning by noting: “A ground invasion is much more difficult for the international community to sympathize with or support……”

These warnings may have serious implications for the future if the recently negotiated ceasefire agreement breaks down. In determining whether or not to invade Gaza, Netanyahu, Barak and Lieberman are confronted with a dilemma. On the one hand, Morsi, the pragmatic Islamist that he is, will not jeopardize Egypt’s annual military aid package of $2 billion from the United States, the $6.3 billion pledge from the European Union, and the $4.8 billion loan just approved by the International Monetary Fund by unilaterally terminating the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty unless he believes that he can terminate the Treaty without financial penalties.

Morsi knows, however, that his views on an Israeli invasion are shared both by President Obama and EU leaders who are concerned about the political and economic backlash in the Arab world that would accompany an Israeli invasion and extensive civilian casualties in Gaza. As Jonathan Halevy writes in the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs: “The fear is that an all-out confrontation would spark an uncontrollable eruption of violence that would endanger Western interests in the Middle East, while also agitating Muslim communities in the West.”

Should the ceasefire agreement fall apart, as is likely, Hamas will no doubt appeal to its Egyptian ally to abrogate the Treaty should Israel invade, and since U.S. and European opposition to an invasion is not expected to change for the reasons noted, Morsi may well decide to abrogate the provisions of the Treaty if he believes that his U.S., European and World Bank benefactors will continue their financial commitments to Egypt because of the Israeli invasion.

This time round, taking into account these two alternatives, Netanyahu determined that the lesser evil would be simply to accept the current ceasefire rather than invading Gaza and risking both American political and financial censure and possible Egyptian termination of the Treaty. In so doing, Israel may have won itself a brief respite from missile attacks on its civilian population, but not an end to the long-term threat posed by Hamas and its Salafist militias in Gaza.

Despite a U.S. commitment to keep sophisticated Iranian missiles out of the hands of Hamas, the threat of a resurgent Hamas supported by Iran remains real. While its capacity to wage war has been seriously diminished, Hamas’s continuing ties with Iran, its genocidal ideology towards Jews and the Jewish state, and its entire socio-political and educational system which is based upon its jihadist pathology remain intact and unaltered. It simply does not have a negotiating position short of the annihilation of Israel and the subjugation of Jews to Muslim rule, as per its Charter, so if Hamas is able to re-arm and re-group despite U.S. and Egyptian assurances to prevent it from doing so, a more dangerous confrontation is assured.

In that eventuality, if Morsi, Obama and EU leaders line up against an Israeli ground invasion (albeit the fact that Hamas is an internationally recognized terrorist organization), Israel will face a Hobbesian choice. It will have to choose between another air operation with limited security goals along the lines of Operation Pillar of Defense or re-conquering Gaza and returning it to the status quo ante. If it chooses the latter, it may not only incur the wrath of the U.S. and Europeans, but facilitate Egypt’s revocation of the Egypt-Israel Treaty that has kept the peace between Egypt and Israel for over three decades. As Barry Rubin writes: ” If the idea of Israel going in on the ground into the Gaza Strip provoked so much international horror, imagine the reaction to Israel overthrowing Hamas altogether.” The moment for making that choice may not be far off.