To Seek a Newer World

“Come my friends,†beckoned the old captain, in Tennyson’s epic poem Ulysses, “tis not too late to seek a newer world….†In this, the first decade of the 21st century, it is more than ironic that a vicious dictatorship holds the key to Middle East peace and stability.

The current debate over Iraq devolves into three fundamental issues – two of which seem to be consuming the attention of the Western World.

–break–

The first issue is whether Saddam Hussein represents a clear and present danger to the Free World. His irrational nature leading to his unpredictability; his history of seeking revenge; his flagrant violation of UN sanctions; his past aggressive actions against his neighbors; his funding of world terrorism; and his dossier (courtesy of President Bush and Prime Minister Blair) – replete with efforts to achieve nuclear capability – strongly suggest that that is so.

The second issue is whether he can be “contained†(to use a “Cold War†term) or whether the only rational solution is to depose him. That decision (whether we know it or not) has already been determined because Saddam Hussein has, on too many occasions, followed “a frightening pattern of bizarre decisions, poor and often irrational judgments, and catastrophic miscalculations involving deeply dangerous moves made with absolutely no assessment of risks or costs,†according to a recent book by Kenneth Pollack – The Threatening Storm: The Case for Invading Iraq. “Containment†cannot work against such an adversary.

During the Cold War era, the concept was based upon the premise that mutual deterrence (through a balance of terror) would prevent the two nuclear superpowers from using their weapons of mass destruction against one another (or against the other’s allies). It worked primarily because both communists and capitalists alike accepted the “illogic†of risking nuclear war. The problem is, Saddam Hussein follows no rules and abides by no such understanding.

But the third issue (representing the centerpiece of the Bush Doctrine – a democratic Iraq and its implications for the future of the Middle East) has all but been lost in the shuffle. While ridding the world of a dangerously armed dictator stands out as the most prominent rationale for regime change in Iraq, it is not the only one. Regime change, with its multiple benefits to the region and to the wider world, will also bring gains to Iraq itself.

Though the risk that Saddam will use weapons of mass destruction against Saudi oil fields (thereby rendering them useless for decades) may alone present a compelling case for action, “there are a number of affirmative factors that also deserve consideration in our assessment of what to do about Iraq†according to a recent article by Thomas Grant of Oxford University.

A functioning secular Arab state: Bernard Lewis, Dean of Western scholars of the Near East, has repeatedly emphasized that Iraq possesses the region’s most secular and best-educated population. The position of women in Iraq at least approximates Western standards. Iraqi engineers are competent enough and numerous enough to have put the country’s infrastructure back in order after the Gulf War. That other members of Iraq’s technocracy use their skills to machine the parts necessary for nuclear armaments only emphasizes the point. What makes Iraq dangerous from the standpoint of its military capabilities also underscores its potential economic viability. What makes Iraq different from Arab countries rife with intolerant radical Islam underscores its potential to become a functioning state in the contemporary global environment.

Oil supply. Iraq exports oil under a UN-monitored system. One half to two thirds of the country’s capacity remains idle under that system — thus removing a major potential source from the world market. With a stable and peaceable regime in Baghdad, the international community could lift the embargo on Iraqi oil — and thus further weaken the grip of OPEC.

Ending an embargo after the regime change, would mean more than doubling the new government’s exports. Assuming a modest dip in the price for oil, the new regime would generate twice as much revenue as under the embargo, and the revenue available to the new government for “useful public expenditures†would increase by an even greater multiple.

Saddam infamously squanders his nation’s wealth. Palaces, by some reports 100 of them, Republican Guard salaries, and crash programs to build and hide weapons of mass destruction absorb the lion’s share of Iraq’s embargo-curtailed income. Lifting the embargo will increase Iraq’s income. Depose Saddam, and the income no longer disappears into the sands of the Iraqi desert.

Regional trade. A post-Saddam Iraq would benefit from a freeing up of its entrepreneurial capacity and a reopening of trade with its neighbors, easing the way toward Iraq’s stabilization and reintegration into the civilized world.

Prior to 1991, Turkey traded extensively with Iraq, while Jordan and Syria, with their smaller and weaker economies, depended on that trade the most. The embargo against Iraq has all but halted trade, except for trickles continuing in the form of monitored exemptions and smuggling. The Central Bank of Turkey estimates that this has cost Turkey $30 billion. The best hope for economic recovery in Turkey and other countries hamstrung by the embargo lies in reintegrating Iraq into the network of regional trade.

Saudi Arabia. A democratic Iraq would facilitate disengagement of U.S. forces from Saudi Arabia. The presence of American military personnel in Saudi Arabia engenders continuing unease in the Muslim world and in Arab countries in particular. American forces, with unveiled women driving jeeps is an affront to the sensibilities of devout Sunnis. Evacuation of American forces from Saudi territory would lessen tensions with Saudi society and with Arabs elsewhere as well. An Iraq without Ba’ath expansionists and with its military pared down would permit American withdrawal from the Saudi peninsula. As such, regime change in Iraq would open the way to end the chief complaint of Saudi radicals toward their leaders and toward America.

Iran. A secular and stable Iraq would present a democratic dilemma for Iran. Caught in a tug-of-war between reformers and radical mullahs, Iran well might benefit if a forward-looking democratic government replaced an old enemy. The result would not be immediate or decisive, but it would be inevitable.

Democratic ripple effect. Today’s terrorists have been betrayed by every political trend of their region for the past half-century: Arab nationalism, Arab socialism and Arab despotism. They are stuck in systems that don’t work, they have no voice, and they blame the world’s only superpower for preserving the status quo they hate and backing the regimes they despise.

The Arabs have tried all sorts of political slogans during this era. The nationalists had the dream of pan-Arab unity. The Islamic fundamentalists had the dream of an Islamic state. As a result, the Arabs are living part of their daily lives in a dream world. They sink into a political Neverland, fed by the backlash to American rhetoric that is eagerly seized upon and spiced up by Arab intellectuals. The leaders of the Arab world are afraid to dispel or challenge those dreams, since they have no way to justify their own ineffective governments.

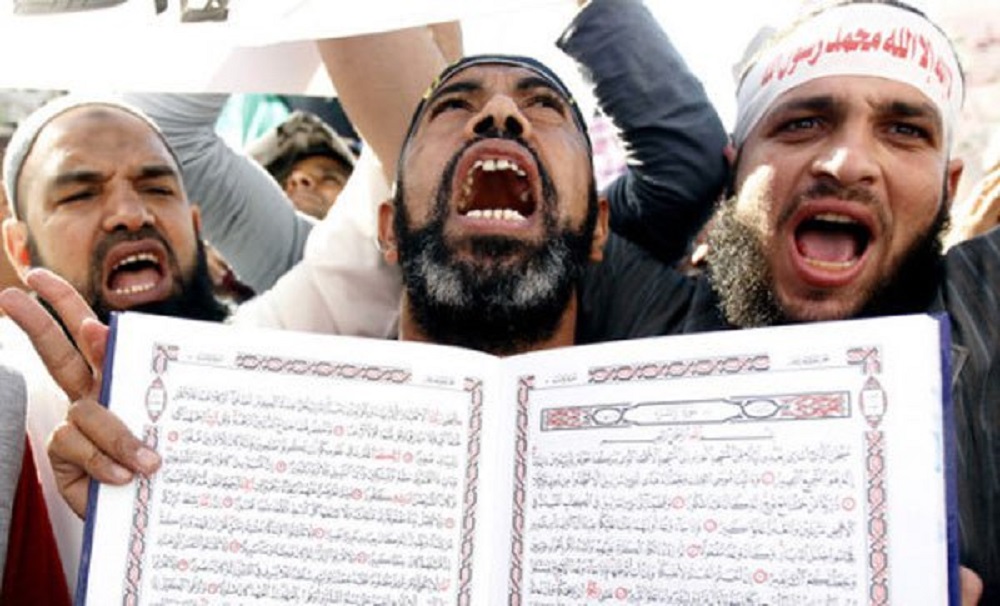

In addition, failures in education and reform have left even the richest Arab states, such as Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf monarchies, bereft of a labor force with the skills to run a modern economy. Failures in civil society have propelled more and more Arabs into the ranks of radical religious movements, whether the Wahhabi sects of the Arabian peninsula, the Islamic Brotherhood of Egypt, the revolutionary guerilla army in Algeria, or the transnational network of al Qaeda.

With the democratization of Iraq, the “contagion†of democracy and democratic values will begin its sweep through the Arab world. The first items on the “new Middle East agenda†will include tackling illiteracy and the disenfranchisement of women. According to a new UN study, prepared by Arab scholars and entitled “The Arab Human Development Report,†in a region that holds the planet’s greatest oil riches, 65 million adult Arabs, two-thirds of them women, are illiterate. Some 10 million children between the ages of six and 15 million are out of school. Less than 1% of the population uses the Internet, and Spain has a greater Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than all 22 Arab states combined.

The wave of democracy that has transformed Latin America, Asia and Eastern Europe the past two decades has barely reached the Arab states. Frustrated young Arabs simply leave. In a poll of older Arab youths, a remarkable 51% expressed a desire to emigrate. Others stay and turn to Islam. And in the version of Islam now in favor in many spots, they are taught that the problems of their world are the result of corrupt Western influences — particularly American ones.

The dictatorships that rule much of the Middle East today will not, indeed cannot, make peace, because they need conflict to justify their tyrannical oppression of their own people, and to deflect their peoples’ anger against an external enemy. A peace settlement would deprive them of this valuable safety valve, leaving them to face the undeflected anger of their subjects, including those who live under the rule of the Palestinian Authority.

According to Mohammed Al-Jassem, editor-in-chief of Newsweek in Arabic, “The Arabs need shock therapy, some kind of tremor that would bring them back to reality and away from their political dreamscape.†Egypt’s loss in the 1967 war against Israel did away with the nationalist slogans prevalent since the July 1952 revolution carried out by Gen. Gamal Abdul Nasser. If the 1967 shock laid the ground for the spread of radical Islam as an alternative to Arab nationalism, the deposing of Saddam Hussein in favor of a democratic, federalist Arab regime might be what is needed to launch a new era of pragmatism.

“Saddam’s fall,†says Al-Jassem, “will cause the Arabs to be shattered psychologically. Political depression will set in. Some Arab regimes will, no doubt, suffer from domestic unrest, triggered by public outrage. Those regimes will find themselves face to face with their people, forced to deal with domestic issues after the United States succeeds in shutting down the last despot who maintained the illusion that Arab slogans can nurture a people. If Washington should also succeed in making the Arab countries mediators in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict rather than parties to a broader Arab-Israeli endless war, then the region will really be transformed.â€

The next stage in Arab history will be one of internal domestic confrontations. After Saddam, not one Arab regime, including Syria and Libya, will dare oppose the United States, and most Arab regimes will be forced to pledge themselves to slogans like “renewal, reform and change†as a way of keeping their frustrated masses at bay.

Action against Saddam, though justified as a means to eliminate a “clear and present dangerâ€, holds promise beyond the added security that would flow from ridding the world of a dangerous tyrant. Post-Saddam Iraq contains potential for local, regional, and global gains of momentous scope. In liberating Iraq, we move the Middle East one step closer to peaceful co-existence.